Meet the rewilders: Dayshul Brake

Tucked away in the rolling pastureland of mid-Devon, an unlikely group of landowners is starting out on a journey to transform their corner of the countryside, in Britain’s first rewilding ‘cluster’.

Ask what a rewilding ‘cluster’ is and you’ll be given the answer that it’s a group of landowners working together to maximise the benefits of nature. Yet the story of Dayshul Brake is one of serendipity, bringing together an unusual mix of three very different characters in an increasingly shared endeavour.

It comprises a local farmer turned forester, a retired psychotherapist and her daughter, and an artist who had a livestock farm land in his lap. Separately and together, these three are slowly creating a patchwork of recovering nature.

It’s early days, but already ponds are bringing life back to drained-out ground, hay meadows sparkle with rattle and eyebright, and kestrels and sparrowhawks spiral over the fields.

The story so far

- Who: A retired psychotherapist and her children, a livestock farmer and a farmer turned forester

- Where & when: Mid-Devon, since 2019

- What: A rewilding ‘cluster’ sharing expertise, seeds, equipment and livestock

- How: Species reintroduction, restoring hedges, grazing herbivores, thinning of conifers, creating new ponds, neighbourhood engagement

- Income – current: Timber and organic meat

- Income – future potential: Government payments for ecosystem services such as ELMs, low-impact tourism and events, community-supported agriculture

- Ecosystem benefits: Reduced flooding, increased biodiversity, soil recovery, carbon storage

Dorette: the catalyst

If Dorette Engi hadn’t read Isabella Tree’s Wilding, which recounts ‘the return of nature to a British farm’, Dayshul Brake might never have come into being.

With retirement looming, the briskly outspoken psychoanalytic child psychotherapist who grew up in Switzerland, was keen to put her strong Buddhist principles into practice for the planet. Inspired by Wilding, “I thought, perhaps a bit presumptively, ‘OK, I’m going to do that’.” Her presumptuousness extended to booking herself on a rewilding course for landowners at Tree’s Knepp Estate. Presumptuous because, as yet, Dorette didn’t own a single acre.

That changed in 2019 when she and her daughter, Eti Meacock, fresh from a permaculture course, and architect son Anthony, bought Broadridge Farm, having scoured the county for suitable sites. “It just felt ideal… It hadn’t been over-fertilised and ‘pesticided’… And it had water. We wanted water”.

They were fortunate enough to be able to draw on the wisdom of several experts including Mick Bracken from the Woodland Trust, beaver specialist Derek Gow, Tom Parsons of the Devon Wildlife Trust and Alastair Driver of Rewilding Britain. Then they set about what Alastair calls,“the sprint at the beginning”. Swathes of non-native conifer plantations were felled – with the advice of Mick and the help of Storm Arwen – and hauled into‘habitat heaps’, to explore whether they could in effect act as a sort of nursery for the recovery of native species, as part of a process of‘natural succession’.

“Someone in the village told me, ‘I hear you’re bringing in giraffes and 12 beavers’.”

A rewilding ‘experiment’

Next, beavers were introduced to a specially-made lodge in the newly-cleared banks of a large pond, which these ‘eco-engineers’ are now reworking, even building one of their characteristic little canals, and giving birth to Dayshul Brake’s first beaver baby. Elsewhere, drains were cut, 25 new ponds dug, and Tamworth pigs brought in to rootle and scuff the land back into life.

It’s this sort of finger-in-the-air exploration which appeals to Dorette. “Wilding is experimental. That’s what I like about it. I love the idea of creating a space, and seeing what it needs. Moving forward without following a strict guideline. I really wanted to play.”

How did locals react to the arrival of this playful experimenter? Rumours were rife, she recalls. “Someone in the village told me, ‘I hear you’re bringing in giraffes and 12 beavers’. So I replied, ‘No, but I am bringing an elephant’”.

Joking aside, they met their neighbours to tell them what they were up to, found little in the way of active opposition, and as Dorette puts it, “what there is, is very nice.”

Evidently, the experiment is working so far. In Dorette’s words, “the land has become so much more alive.” Around 10 trail cameras, installed mainly by Eti, capture the revival. Badgers, hares and hedgehogs abound, and smaller creatures, too, are thriving: harvest mice and water voles (both introduced) and dormice, nurtured through nesting boxes. Bird life includes everything from barn owls, wheatears, skylarks and blackcaps to tree and meadow pipits.

Olly: reinvigorating the soil

Dorette met second cluster member Olly Walker when several of his Red Ruby cattle broke into her land the day she moved in, with him chasing after.

A boyish, softly spoken 40-something with a ready smile, he looks far too unruffled to have four children under 12, let alone to be running a 98-hectare livestock farm.

Like Dorette, Olly wasn’t born into agriculture, although a rural childhood involvement with the local Wildlife Trust meant he grew up “immersed in green”. Then in 2013, after studying fine art and working in a creative social enterprise, “the bombshell dropped”. His mother-in-law presented him with a fantastic offer. “She owned this farm – Essebeare. Its tenant was retiring. How would I like to come and run it?!” Olly jumped at the chance, forming a partnership with his wife and mother-in-law, with him as majority shareholder.

The challenge was irresistible, he says. “It’s an ancient farm – it’s in the Domesday Book. Fifty generations of people have worked these fields.” Like the rest of the cluster, it hadn’t been intensively managed in recent years, and so was ripe for regeneration.

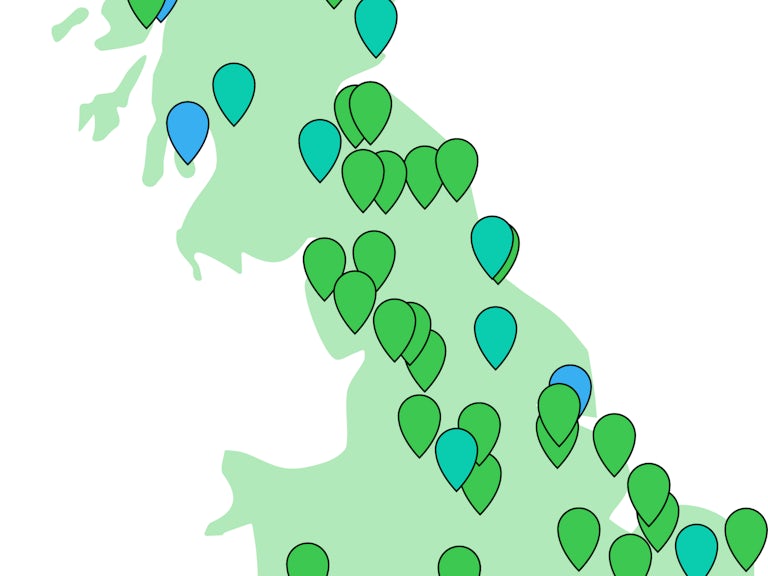

The Rewilding Network

Dayshul Brake is part of our Rewilding Network, the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

“This ancient moorland was brought into production against its will, post war. So it’s wonderful to see the life returning.”

Resolved to speed that process, Olly studied agriculture, worked on organic farms, and then set about converting Essebeare, gaining organic status in 2018. “I call it the 50/50 project. Fifty percent of the land at any one time is in agricultural production, and 50% in restoration.”

Carefully managed mob grazing, in which the farm’s 180 breeding ewes and 85 cattle rotate around patches of pasture, allows restored hay meadows up on the hills to flourish. They sparkle with sheets of buttercups, sprinkled with orchids, eyebright and yellow rattle – the so-called ‘meadow maker’, because of the way in which it suppresses grass growth and so makes space for wild flowers to thrive.

Working with advisers including Mick Bracken, Olly is carefully managing a patch of coppiced woodland, which acts as a ‘green barn’ for sheep to shelter from the weather, and planning a wider agroforestry strategy.

Meanwhile, he’s also restored over 2,000 metres of bulldozed hedge banks, and created another 1,250 metres from scratch, with more to come. Elsewhere on the farm, he’s allowing what was once grazing land by the river to sprout willow and alder, sporadically browsed in short bursts by his livestock.

But the biggest impact is happening out of sight, below the surface. “My key goal in farming is to reinvigorate the soil, restoring organic matter, and rebuilding that to feed the biome”.

Val: a quiet transformation

While Dorette and Eti are fresh arrivals, 77 year-old Val Green, whose land abuts Dorette’s, has lived there for nearly 50 years. During that time, she’s overseen a quiet transformation which has helped nurture something of a natural revival, too.

She and her late husband Tony, initially along with his father and brother Philip, ran a typical mixed Devon farm, but by the mid-90s,“we were fed up with never going anywhere, never doing anything. We hadn’t had a holiday for 30 years.” They shifted into forestry – planting their land with a mix of conifers and broadleaves. All that is, except for a little 10-hectare jewel of Culm grassland.

A south-western speciality, its unique combination of purple moor grass and rush pasture sponges up carbon and water alike, helping prevent flooding downstream. Much work has been done by the local Wildlife Trust to quantify the value of these‘ecosystem services’, and Val is visibly proud of its precious flora and rare species, including the marsh fritillary butterfly.

For years, she and Tony had already been thinning out conifers, favouring the broadleaved trees and doing their best to care for the Culm. Now as part of the cluster, Mick Bracken is helping her create new management plans for her woods, and she’s putting in ponds and scrapes.

Listening to Val, it’s clear that becoming part of this shared adventure soon after Tony passed away in 2019 has offered something of a personal revival, too.

The cluster effect

Today, Olly’s Red Rubies are crossing the boundaries deliberately, to help bring new life back to Dorette and Val’s land. And the Tamworths will soon do the same.

It’s not only livestock that these three friends and co-wilders are sharing, but wildflower seeds, tools and machinery as needed and, potentially one day, volunteers. They are also creating a joint digital map of habitats and key landscape features to inform more strategic decision making across their holdings.

Their collaboration is still in its early days. As Eti puts it: “We’re exploring our joint vision and what it means to be a cluster. So far, it’s happened quite organically.”

All three members are keen to press ahead with rewilding, but the costs can be daunting. As Val says: “We’re not rich farmers; we can’t just spend without getting any funding to help.” Olly agrees. “We’re not landed gentry. I have to work ridiculously hard, as most farmers do, just to make ends meet. Ultimately, I run a business, which has to stack up.” Even Dorette and Eti, relatively flush from inheritance and the sale of a London home, aren’t insulated from the need to make a living. “We have to turn a profit within five years”, says Dorette. They have plans for some low-impact tourism, and converting a barn into a venue.

Olly, meanwhile, is focused on marketing his produce direct online, “telling the story of what we’re doing here”. He’s also exploring a CSA (community-supported agriculture) model, too. “It would be really good to be working more on a local scale.”

The three share a conviction that they’re providing valuable ecosystem services – just the thing that the government has repeatedly said it wants to support as, post-Brexit, it shifts away from the area-based payments of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

Ecosystem rewards

Even in its early days, the benefits of the work undertaken so far are already apparent. “I’m doing a lot by not farming here”, explains Dorette. “The water stays on the land [helping prevent] floods.” Olly confirms the impact. “Since these guys came, the river hasn’t burst its banks like it always used to, and the flow of water has been drastically reduced. It makes a huge difference, having that ‘sponge’ upstream.”

Olly has had some grant funding from the Higher Level Stewardship programme, but for the most part the three have received precious little state support. “So”, concludes Dorette, “it would be nice if the government pays us something for all the services like that which we provide for free!”

Which is where the cluster idea may help, since it looks as though funding will increasingly be directed to larger areas of nature restoration than a single farm. The Dayshul Brake crew are already looking beyond their patch too, starting to talk to neighbouring farmers and landowners about creating a natural corridor between Devon’s two great moors, Dartmoor and Exmoor. They feel there’s ample potential for collaborating to nurture a mosaic patchwork of a landscape, brimming with ecosystem services.

As Olly puts it: “This is ancient moor ground, all of this, and with all the intensification post-war, it was really brought into production against its will. So it’s wonderful to see the life returning. It’s the right thing, you know, the right thing that’s happening here.”

Published January 2023

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network