Impact story: Kingsdale Head

Supported by our Rewilding Innovation Fund, the team at Kingsdale Head has been growing native mosses that will help restore and protect their damaged peatlands.

At Kingsdale Head, a former sheep farm turned rewilding project in the Yorkshire Dales, the team has been growing native mosses that will help restore and protect their damaged peatlands, supported by our Rewilding Innovation Fund. The project’s Conservation Manager Jamie McEwan opens the door to the propagation barn and uncovers the secrets of these delicate plants, their role in capturing carbon and the twists and turns of growing them.

“The good thing about sphagnums is you can put them back and restore a nice healthy layer of bog vegetation, protection for that big layer of carbon underneath.”

Jamie McEwan

Kingsdale Head

From a distance, peatland might not look like a diverse or environmentally important ecosystem. But its spongy hummocks and pools are teeming with rare species quietly playing crucial roles in controlling greenhouse gases, floods and droughts. These fragile landscapes have been damaged by hundreds of years of human activity; restoring them is an urgent, nature-based solution to the twin crises of climate breakdown and biodiversity loss.

Far in the uplands of the northwest Yorkshire Dales, Jamie at Kingsdale Head — along with site owners Tim and Catherine — has been working hard to boost blanket mosses and restore the 450 hectares of peatlands they protect. Like most UK peatlands, the bogs at Kingsdale Head were drained to improve grazing for sheep. Combined with air pollution stemming from the Industrial Revolution, this caused native moss species to decline — sometimes disappear — and damage the peatlands, putting the carbon stored in them at risk of release.

Kingsdale’s mission is to regenerate this 607-hectare former sheep farm into a flourishing landscape of peatlands, woods and wetland habitats, restoring biodiversity and carbon capture and storage. To help restore the peatlands, Jamie has been leading a project to grow and transplant a rare native sphagnum moss species, made possible by our Rewilding Innovation Fund. We spoke to him and discovered the rewilding ripple effect of this propagation venture.

What are sphagnum mosses and what’s special about them?

Sphagnum mosses are these keystone species that drive a lot of the processes on blanket bogs, including peat formation. They create this kind of sheltered micro-habitat for invertebrates in a really exposed situation. And they can hold multiple times their own weight in water. 400 hectares of up to 30cm-deep sponge, you can imagine the impact that has on rainwater hitting the streams, controlling flooding. During droughts, you’ve got that trickling of water from the mosses.

Without these sphagnum, you’ve got less structure and the peat soil underneath is more susceptible to erosion. When water hits that peat, it’s running straight towards the rivers and not being attenuated in the vegetation. When you’ve got a healthy blanket bog you’ve got resilience in the hydrological system.

The point of peat

Peatlands are waterlogged, acidic habitats that form over thousands of years. Peat forms when dead plant material is too waterlogged to decompose. The plant fragments steadily accumulate to form a waterlogged, compacted mass of carbon-rich material — peat. While any plant can become peat, sphagnum mosses are vital to the formation and maintenance of these crucial carbon stores. They grow from the top and die at the bottom, leaving dead material in the waterlogged zone. The living part can acidify its surrounding environment, further slowing decomposition and promoting peat formation.

The peatlands of northern England and Scotland hold more than three times the carbon of all UK woodlands. When peatlands are drained for farming or mosses die, leaving peat exposed, the carbon is released as carbon dioxide. Protecting and restoring the UK’s peatlands is urgently needed to mitigate climate change and restore biodiversity.

Why did you choose to reintroduce sphagnum austinii in particular?

The good thing about sphagnums is you can put them back and restore a nice healthy layer of bog vegetation, protection for that big layer of carbon underneath.

In North Yorkshire a huge amount of that really important carbon store on our upland sites was formed by two species—austinii and fuscum—that we just don’t have on site or in Yorkshire anymore. The peat cores show they were present all the way up to the Industrial Revolution and then were lost for most upland bogs in the north of England. We thought it was important to investigate whether it was possible to bring them back to site.

What has the Rewilding Innovation Fund enabled you to do?

There wasn’t enough austinii or any fuscum in England to just translocate, so we needed to find a way to propagate them up. The Fund enabled us to re-clad one of our old sheep barns with polycarbonate so we could use it as a growing space.

Then we needed to collect some austinii, which involved identifying it, getting consent and then taking some. There were a few hoops to jump through and quite a lot of survey work. Thanks to the Fund we were able to pay for support from The Yorkshire Peat Partnership to help with that.

We’ve been able to propagate about 10 trays now. We’d normally plug chunks of individual plants straight into the soil, but austinii is quite a sensitive species, so we’re keen to put them out once we’ve got a good healthy hummock growing, to give it the best chance.

There’ve been lots of great outcomes from using that space in other ways too. We’ve been practising different methods for sphagnum propagation with more common, tolerant species from the site. We grew about 5,000 sphagnum plugs that we sold to another restoration project.

What have been the project’s biggest successes?

As well as giving us that opportunity to experiment with reintroduction and propagation, we’ve been able to use the barn flexibly and generate a little bit of revenue. We have about 10,000 plugs of other species growing. As a result, we’ve employed somebody for a day a week to manage some of the propagation alongside other bits and pieces.

We’ve also got 110 montane trees growing in there and some other tall herbs. We’ve got a wee bit of funding to grow on some of those trees and reintroduce them, to improve habitats.

I’ve been keen to demonstrate an alternative use for upland farm buildings. If land use changes enough in these areas, there are still huge amounts of farm buildings that people often have money invested in. It’s been useful to be able to look at uses for indoor spaces that would otherwise be redundant and demonstrate that they’re viable.

We’ve also hosted education groups in the barn — we’re one of the stops on the Yorkshire Peat Partnership’s accredited peatland restoration practitioner course.

The project outcomes

- Conversion of an otherwise redundant upland barn into propagation space

- 10 steadily growing trays of rare sphagnum austinii

- A new employee, funded by selling 5,000 propagated sphagnum plugs

- 10,000 more sphagnum plugs ready for sale

- 110 montane trees and other tall plants grown to reintroduce on site

- Community engagement through propagation

- Hosting of peatland education groups

- Further funding unlocked for propagation

- Insights gained that can be shared with other rewilding practitioners

How have you involved the local community?

Historically it’s been difficult to get people involved in peatland restoration because it’s quite remote, with helicopters and diggers usually doing the heavy restoration work. We’ve used various groups of volunteers to do some propagation and that’s the first time we’ve been able to bring people up to be involved directly in peatland restoration works.

It’s quite hard to describe peatlands. They function quite differently from other habitats, and from a distance they don’t always look that exciting. Getting people involved in sphagnum growing has been a good way to engage people in peat restoration.

“Getting people involved in sphagnum growing has been a good way to engage people in peat restoration.”

Jamie McEwan

Kingsdale Head

What are your next steps and hopes for Kingsdale Head?

I am pleased we’ve grown the austinii, but we had hoped to have introduced it to the site already. We’ve been able to grow other species quite quickly, but austinii grows slowly. It’s proving to be quite a delicate wee plant; they’re clearly quite sensitive. So the hope is to get 10 resilient hummocks of austinii that we can put straight onto site. Once we’ve got some happy hummocks, we’ll try different ways of introducing them and monitor the success. In the longer term, we’ll be able to grow them on for our site and potentially others and advise other practitioners on the best way to reintroduce austinii to other sites too.

One challenge for us was that we could only take a small amount of austinii from the Pennines source site without damaging the hummock, which was only a small population and the last local site. One way to potentially overcome this is a method called micropropagation, where you blend the plant then grow it in a medium. You can grow quite a lot from a small amount, so it could be a good way to quickly propagate from a small population. This might be one of the methods we test and share with the Yorkshire Peat Partnership, who plan to work with community groups to grow sphagnum. As well as being a learning resource for that project, the Partnership might continue to buy our plants.

In the past five years, lots has changed in our area, it’s quite an exciting place to be. There are other big environmental projects in the uplands, all doing some quite big and exciting things. We’re not on our own.

The Rewilding Innovation Fund

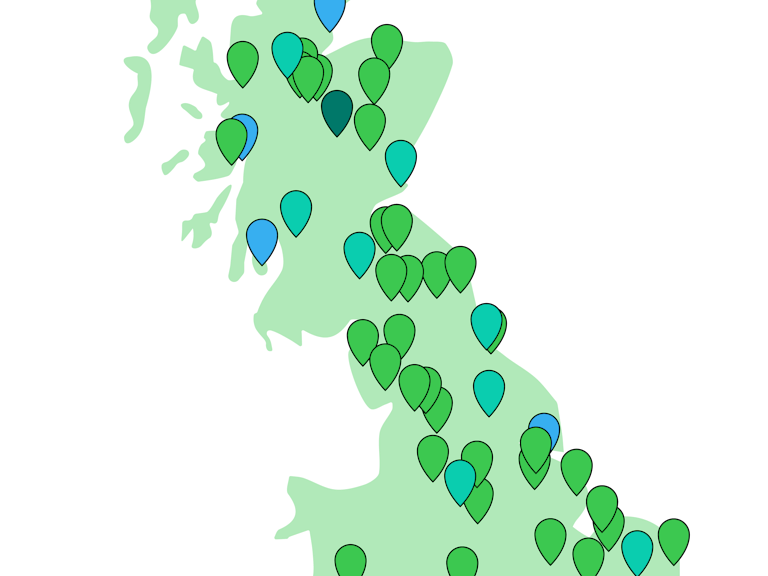

Kingsdale Head, a member of the Rewilding Network, is just one of the 60+ projects that we’ve funded through the Rewilding Innovation Fund, helping to enable the large-scale restoration of ecosystems across Britain.

See all the beneficiaries.

Be the change

Join the movement

Keep up to date with Rewilding Britain’s campaigns for change by joining our mailing list.

Sign up to our newsletter

The Rewilding Network

The Rewilding Network is the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Discover the Rewilding Network