Meeting the giants of the Spanish plains

Published 22/10/2025

Rewilding Manager Sara King takes inspiration from the ecosystems and communities shaped by the bison reintroduced to southern Spain as free-roaming wild animals. She asks: why not in Britain?

“We didn’t know all the answers before we introduced the large graziers, but we’re learning a lot now that they’re here.”

Fernando Morán

Director of the European Bison Conservation Center of Spain

I recently visited the vast estates of southern Spain to understand more about the European bison that have been reintroduced. As part of the Large Herbivore Working Group – a collaboration of eNGOs, consultants and landowners who are working collaboratively to integrate wild herbivores into the UK – I wanted to see how they’re managed, their impact on wildlife and ecosystems and how we can apply these learnings to Britain.

The plains where rewilding was taking place were absolutely stunning. We visited several viewpoints where they stretched as far as the eye could see. To kickstart natural processes across them, estates are taking several approaches, including restoring hydrology where possible, through river restoration and pond creation, and species reintroduction. Not only have bison been reintroduced in several estates over the last couple of years, but one also supported a herd of semi-wild Przewalski’s horses and two others have recorded the rare Iberian lynx.

The major difference between the bison reintroduction celebrated here in Britain at Wild Blean and these Spanish reintroductions is that, even though estate boundaries are marked by fences, the bison in Spain are classified as wild animals. In Kent they’re classified as livestock.

This means that these free roaming bison are medically treated if needed, but aren’t subject to livestock regulations so don’t require regular TB testing or ear tags. It also means that, when they die, their carcasses can be left on site, providing food for wolves and vultures. (Learn more about the importance of this in our article How death gives life.)

A bison-sized impact

What struck me most on the trip was the sheer abundance of wildlife. We spotted mongoose, evidence of wild boar and lynx, bison, Przewalski’s horses, frogs, pond turtles, kingfishers, eagles, goshawk, peregrine falcons, and wild flamingos, to name but a few. And hundreds of vultures. I found myself in a national park straining my head back to see the hundreds of vultures soaring and circling above my head riding the thermals, looking for one of the carcasses in the landscape to clean up and scavenge.

The presence of the bison has also had a big impact on other elements of the ecosystem. Grazing from the bison has created better forage for rabbits. More rabbits means a better prey base for the Iberian lynx. Although we weren’t lucky enough to spot one of these elusive ambush predators, there were eight lynx territories supported within one of the sites. I expect they saw us even if we didn’t see them…

Several of the estates have also reported a lower level of disease within their wild deer populations compared to neighbouring estates. More research is needed, but healthier fully functioning ecosystems appear to be creating more resilient wildlife – more crucial than ever as we witness the impact of extreme weather and climate heating.

That was clear when we visited a site that had experienced a wildfire the previous year. Thanks to the bison, the fire didn’t burn as intensely as on surrounding estates. Their grazing and browsing had created a varied vegetation structure, reducing the fuel load and resulting in a faster burning fire that’s therefore less intense and so less damaging. We could barely see evidence of the fire on site, the vegetation has recovered so quickly.

Lessons for Britain

There are so many learnings that we can draw from projects in mainland Europe who’ve already reintroduced these animals, despite the differences in our landscapes and culture. Here’s what stood out for me.

We need joined-up thinking

Some of the vast areas of natural habitat in Spain we saw could probably support hundreds of herbivores on a level seen in the Serengeti. We simply don’t have this space in Britain. Nevertheless these estates show how herbivores like bison could catalyse bigger thinking – for example joining up landscapes with green bridges or landowners creating shared visions for a region. We need to get these animals into the environment – we won’t know all the answers, but we must try new things and be innovative and bold.

Bison mean ecosystem resilience

The habitats of Spain are also very different to Britain. Unlike the arid prairie landscapes we explored, Britain is much wetter with more woodland/scrub mosaics. Yet we can still draw parallels when looking at the potential impact of large herbivores on ecosystem resilience, particularly in relation to disease, fire and drought. There’s no denying that when large herbivores are returned to the landscape they have an impact on other wildlife and natural processes.

The Rewilding Network

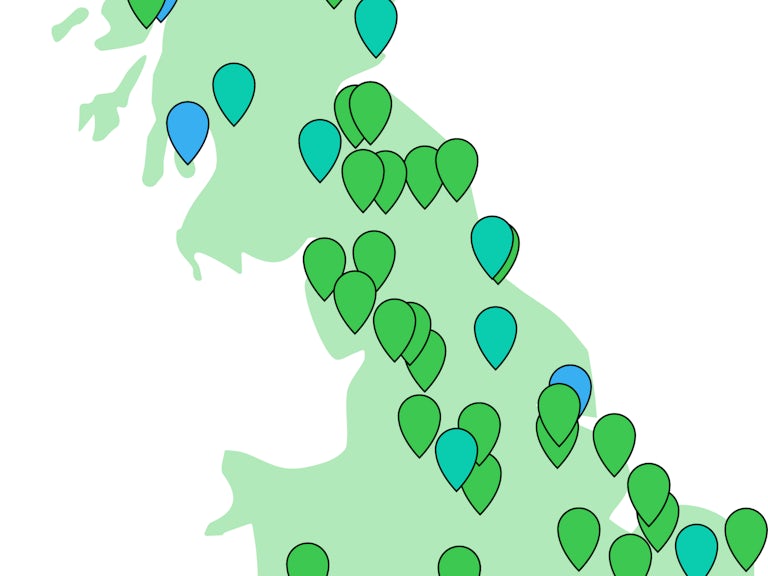

Through the Rewilding Network we bring together rewilders from across the three nations so they can connect, inspire and support each other to create a wilder Britain that benefits us all.

Large herbivores are natural firefighters

With the hotter, drier conditions we’re seeing in Britain bringing an increasing number of wildfires, we can learn a lot from Spain’s herbivore reintroductions. As we witnessed on the trip, grazing and browsing by large herbivores can create healthier, more diverse ecosystems that are more resilient against the effects of extreme weather events like wildfires.

Free roaming wildlife can work

Thirdly, the large herbivores in Spain are not behind fences with no access. We were able to see and observe the bison with no barriers between us. The bison and Przewalski’s horses were both curious about us, but there was never a moment where we felt in danger. We kept a safe distance at all times and maintained respect. There’s no reason why we can’t have landscapes in Britain where species are free roaming.

People can benefit too

We met the most amazing people who were living, working and enjoying the rewilding estates. Everyone we spoke to was enthusiastic about the wildlife they were working with – lynx, Przewalski’s horses, bison and so much more. And that was in an area with a very strong hunting culture, where deer and wild boar are managed as game. These same hunting estates have welcomed the return of wildlife, including bison and lynx. They’re proud to support the conservation initiatives and want to see these animals thrive in the landscape. We must see ourselves as part of nature, not apart from it.

We must learn as we go

The overarching message during the trip was that we’ll never know everything before introducing an animal or restoring a natural process, but that we can and must learn as we go. As our guide Fernando Morán, director of the European Bison Conservation Center of Spain, said to us: “We didn’t know all the answers before we introduced the large graziers, but we’re learning a lot now that they’re here.” We are in a climate and ecological emergency, and Britain is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world (1). The worst thing we can do is to be immobilised by perceived risk and continue with business as usual.

Seeing bison in Spain has given me hope that more large herbivores can be returned to Britain, restoring our ecosystems and providing a wilder landscape for everyone to enjoy. We can only achieve this if we think bigger and wilder.

Join the Rewilding Network

Be at the forefront of the rewilding movement. Learn, grow, connect.

Join the Rewilding Network

- State of Nature Report 2016 ranked UK 189 out of 218 countries