Impact story: Seawilding

Supported by our Rewilding Innovation Fund, Seawilding’s internship programme is training up the next generation of marine rewilders, giving young people a leg-up into a sector that’s making a real difference to the restoration of our seascapes.

Seawilding is the UK’s first community-led native oyster and seagrass restoration project. The team, based on the west coast of Scotland, is reintroducing native oysters and seagrass in Loch Craignish and Loch Broom to restore biodiversity, sequester carbon, create green jobs and mentor other community-based groups.

Tiziana Tedoldi, Seawilding’s General Manager, takes us beneath the surface of the blossoming internship programme bringing fresh ideas and skills to the project, supported by Rewilding Britain’s 2024 Rewilding Innovation Fund.

“It’s so encouraging to see these young students wanting to make the world a better place. It’s a very reassuring bit of positivity.”

Tiziana Tedoldi

Seawilding

The briny waters of picture-perfect Loch Craignish on the west coast of Scotland haven’t always been as healthy as they might seem. By 2020, the seagrasses and oysters key to biodiversity and water quality were seriously depleted by human activity; the Loch was in poor ecological shape. Seawilding is turning this around. Powered by volunteers from the Loch community and far beyond, the native species are bouncing back.

Over the past few years, young interns from across the UK have become a key feature of Seawilding’s work, from practical activities out in the Loch to research to volunteer management. “I think the type of person who decides to become a marine biologist or marine conservationist, you do it because you want to make the world a better place,” says Tiziana, contemplating Seawilding interns gone by. “I think that makes you a really special kind of person.”

The programme offers young marine biologists and conservationists a rare chance to gain valuable snorkels-on experience of marine conservation and rewilding. Its popularity is booming. We spoke to Tiziana, who explained why it’s so sought after and reflected on the interns’ crucial roles in Seawilding’s projects.

Why is Seawilding restoring native oysters and seagrasses?

Native oysters are incredible water filters – an adult can filter 240 litres a day. They also create complex reefs, incredible habitats for a lot of marine life. And they stabilise the sediment, so for coastal erosion it’s really important they grow into reefs metres high.

Seagrass is the only flowering sea plant. It photosynthesises, so it creates a lot of oxygen and captures carbon within its root system, burying it in the soil where it can remain for thousands of years. It’s also an important nursery – fish go into seagrass to spawn and a lot of juveniles live among it before going off into deeper water. But it’s endangered – 92% has been lost across the UK.

So little is known about what happens underneath the water. Even within our loch, everything looks picture perfect from the surface, but once you start delving underneath, you realise things aren’t as good as they should be.

Seagrass meadows cover 0.4% of Loch Craignish but host 68% of the biodiversity. If we could bring back seagrass to what it used to be, the difference it would make in terms of fish numbers, seabirds coming to eat the fish and the crabs, everything associated with the seagrass meadow… it’s a game changer.

What has the Rewilding Innovation Fund enabled you to do?

The Fund supported us to bring three interns to work with us for four weeks. Our interns are an integral part of our active restoration. They get involved in every aspect of seagrass and oyster projects: harvesting seagrass seeds; planting seagrass plants; scrubbing oysters; counting oysters; weighing and measuring them. They research scientific papers for us. They help coordinate volunteers. We put them through snorkel training so they can come out and survey and monitor and leave with snorkelling qualifications. They do so much.

We have six interns this year, double the number of previous years, so the programme is going from strength to strength. Having Rewilding Britain’s backing has definitely helped spread the word about it and we’ve seen a huge increase in applications recently.

Why did you want to bring young people into your team?

There aren’t that many opportunities for young undergraduates to get involved in marine restoration unless, for example, you go and do reef conservation somewhere abroad, for which you pay a tonne of money. We wanted to put together an opportunity for people to get hands-on in what we were doing, but also make it affordable and open to everybody, regardless of socio-economic background. We give them a per diem of £20 and we cover their accommodation.

The first year was just three students getting in touch asking if they could intern with us. The second year we had something like 15 people apply. The third year we’ve had 75 applicants from 9 countries. So it just shows the value of providing something like this. Whittling down the applicants has become challenging! Reading a lot of CVs and then trying to scale them down is really difficult, then trying to get from interviews to offers is even harder because they’re all so bright and passionate.

Impacts & benefits

For Seawilding:

- Crucial practical support

- Fresh perspectives

- Research that boosts knowledge base

- Appealing funding option created

- Marine rewilding network expanded

For interns:

- Practical marine conservation experience to kickstart careers

- Valuable new skills

- Professional connections

How have the interns benefitted Seawilding?

They really help us a lot and we learn a lot from them too. Fresh perspectives on what we’re doing are really useful. Some have finished the internship and decided to do their master’s or thesis on seagrass and oysters, which is great because the knowledge then comes back to us.

It’s also added to the Seawilding story, which makes us an appealing recipient of donations and funds. We tend to present Seawilding as a whole, except the internship programme. So, if donors want to fund something specific, we can offer them this package.

We’re very grateful that we received the funding for this. It’s a really valuable experience that we’re giving young people, but it’s also really valuable for us. It’s so encouraging to see these young students wanting to make the world a better place. It’s great to see that is still alive and well in the next generation. It’s a very reassuring bit of positivity.

Damson’s experience

“This has been one of the most rewarding, hands-on and inspiring experiences. The month was the perfect blend of practical and academic work, and we were able to bring our own knowledge to the projects. The experience for a student or graduate coming here is invaluable to career development and will surely put us in great stead for the future. The chance to see and provide our own insights on practical restoration methods in the field, for this length of time, is difficult to come by in this industry and I am grateful to Seawilding for this opportunity.”

What community outreach do you do and why?

A lot of what we do is supported by the local community, they get very involved. That sense of ownership and stewardship of their coastal waters and being able to get hands on and make a difference is hugely important for mental wellbeing. People also travel quite far to volunteer, because it’s such an amazing experience. We’re always so humbled when people come to help us out and we see how far they’ve come, or how passionately they feel. We get PhD students coming to do quite a lot of research in the loch… it’s like a live marine lab. The UK science on seagrass and oysters is still very much in its infancy, so we’re very open with them and other rewilders, particularly about the failures. We need more people doing this sort of stuff and to encourage people to apply to the UK what they’ve learned in our projects.

Citizen science is an important part of our work, trying to raise awareness of the importance of marine restoration and bringing back lost biodiversity in mitigating climate change. We work in primary schools doing citizen science activities with our oysters and have a youth group called Seawildlings with children from the peninsula. We joke about creating the marine biologists of the future, but you can see some of them really love it, they feel a real connection to the sea.

“For a wilder future, it’s crucial to build blue knowledge and skills today. We’re so pleased to be supporting Seawilding in leading the way, providing local and accessible opportunities to upskill tomorrow’s marine rewilders.”

Jacques Villemot

Marine Rewilding Policy and Advocacy Lead, Rewilding Britain

Is there anything you plan to do differently?

We’ve been having real problems with the supply of spat – baby oysters. Native oysters are quite difficult to grow, and the UK hatcheries haven’t been having success. We’re getting about 10% of the number we’d ideally want, so we’re looking at how we can overcome that, maybe trialling a hatchery in our loch.

What are your hopes for the future?

We’ve really turned a corner with seagrass restoration. After quite a few years of seeing failure in seed germination and translocation of plants, we’ve seen incredible growth. I think this is probably the first time we’ve seen success in the UK at this scale. It’s really exciting.

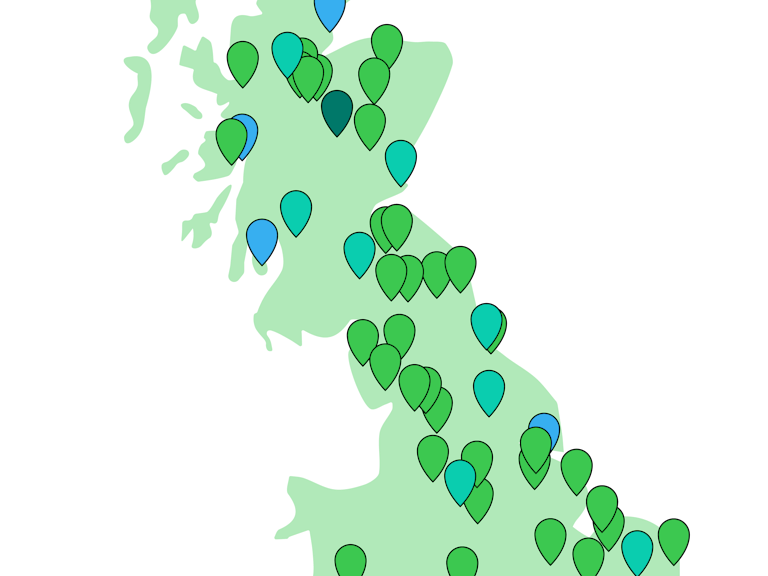

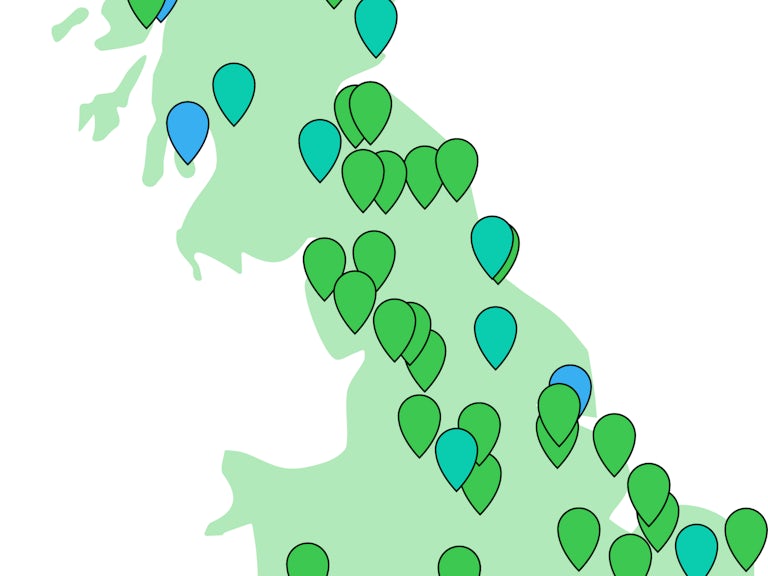

Now we’re thinking about how we can replicate that across the rest of the UK, starting with Scotland. My hope is to see success with seagrass rolled out, scaled up. We train quite a few community groups. When we started out there were three native oyster projects and now there are about 15 – we’ve trained a lot of those. Bringing back lost biodiversity is our end game. To see seagrass projects and native oyster projects all over the UK would just be amazing.

The Rewilding Innovation Fund

Seawilding, a member of the Rewilding Network, is just one of the 60+ projects that we’ve funded through the Rewilding Innovation Fund, helping to enable the large-scale restoration of ecosystems across Britain.

See all the beneficiaries.

Rewilding superstars

Oysters:

- Improve water quality

- Create reef habitats, boosting biodiversity

- Store carbon

- Stabilise sediment, reducing coastal erosion

Seagrass:

- Releases oxygen into water

- Captures carbon in its roots

- Acts as a fish nursery

- Provides habitat for marine life

Be the change

Join the movement

Keep up to date with Rewilding Britain’s campaigns for change by joining our mailing list.

Sign up to our newsletter

The Rewilding Network

The Rewilding Network is the go-to place for projects across Britain to connect, share and make rewilding happen on land and sea.

Discover the Rewilding Network