Our national parks are 70 years old this week. Now let’s make them wilder

On the 70th anniversary of our national parks we celebrate and reflect on their role in restoring and nurturing nature.

Published 15/04/2021

On 17th April 1951, the Peak District was inaugurated as Britain’s first national park. Seventy years on, and with 15 national parks now established in England, Scotland and Wales, it’s a moment to celebrate some of our most cherished landscapes.

But it’s also a time to reflect on their future because our national parks, while containing many breathtaking views, are mostly ecological shadows of what they could, and arguably should, be.

At Rewilding Britain, we have a vision for wilder national parks that are full of thriving wildlife and restored habitats, leading the way towards a wilder Britain. The question is: how can we get there?

A new designation

In 1951, the national park was a new designation flowing from laws passed two years previously. As originally conceived, national parks had two crucial purposes. First, they would protect some of our most precious landscapes from urban sprawl and industrial encroachment. And second, they would enable public access to the countryside, acting as a ‘natural health service’ (to sit alongside the new NHS) where Britain’s city-dwelling populations could stretch their legs and breathe in fresh air.

These twin purposes remain vital today. The past year of lockdown restrictions has shown just how much we all need access to green space.

But over the decades, the shortcomings of our national parks have become increasingly clear. The national park designation is based on landscape protection, not nature protection. The difference may seem subtle, but in fact it’s fundamental. Our national parks help protect rolling hills and open countryside, but they do little to protect and restore biodiversity.

“Research shows that nature in our national parks is not in good shape”

Nature in our national parks

In the US, the Federal Government owns vast swathes of protected public lands, including national parks such as Yosemite and Yellowstone. In the UK, most of the land in our national parks is privately owned. National Park Authorities (NPAs) can therefore use their planning powers to restrict building and development within their boundaries but they have very few powers over the wider landscape to encourage nature recovery.

As a consequence, research shows that nature in our national parks is not in good shape:

- Studies by RSPB and Friends of the Earth (FoE) found that on average just 26% of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) within England’s national parks are in favourable condition. In fact, SSSIs are in a worse condition inside our national parks than outside them.

- Analysis by FoE revealed that woodland cover in some of our national parks is below urban levels – with the Yorkshire Dales, for instance, having lower woodland cover than London.

- A recent film by geographer Dan Raven-Ellison , The UK’s National Parks in 100 Seconds, illustrates how much our national parks are dominated by overgrazed pastures, grouse moors and plantation forestry. In four national parks, pasture accounts for over half the land, while more than three-quarters of the South Down national park is agricultural.

But there are tantalising signs that change is coming.

Wild for people

The public have long wanted to see wilder national parks. An in-depth 2016 survey asked people what changes they wanted to see in national parks in future: ‘better conservation of wildlife’ and ‘make them wilder’ were the top responses from visitors and residents alike.

Rewilding Britain has been calling for ‘wilder areas’ in our national parks for several years. Our director, Alastair Driver, first wrote in 2018 about the idea of devoting at least 10% of our national parks to be ‘wilder areas’. These would be areas of land where natural processes are being restored and nature allowed to really thrive.

In 2019, the Glover Review – a UK Government-commissioned report into the state of our national landscapes – recommended that in future, national parks’ management plans ‘should set clear priorities and actions for nature recovery’, including the creation of ‘wilder areas’.

We’re still waiting for a UK Government response to the Glover Review to see if ministers will take up these recommendations. Even if they do, much more work is going to be needed to give this proposal some bite.

Change is coming

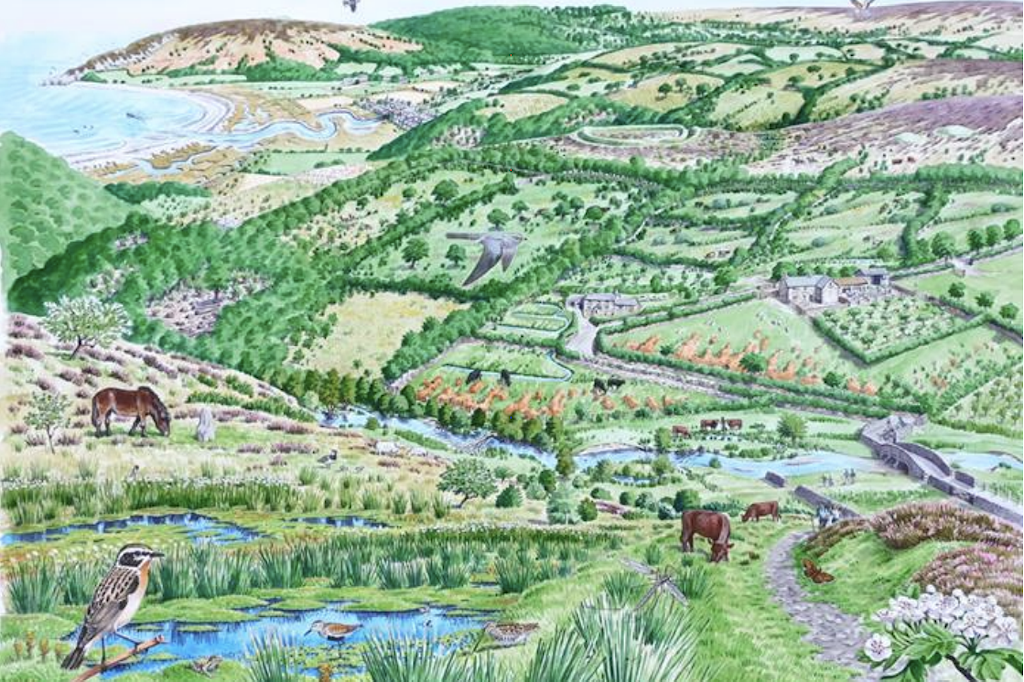

Encouragingly, some NPAs are already starting to make their own suggestions for what wilder national parks could look like. Last November, Exmoor NPA voted through a ‘nature recovery vision ’ which included plans to:

‘Create 7,000 hectares of ‘nature recovery opportunity areas’ where nature and natural processes are allowed to take their course. In these wilder areas land will be allowed to recover, healthy soils and clean water will be restored, and wildlife will recolonise (10% of the National Park).’

The vision was accompanied by two images illustrating how Exmoor looks today, and how it might look in a wilder future (see above).

Exmoor’s vision is brilliant – and some other NPAs are now following in their footsteps – but we won’t get wilder national parks across the board unless ministers mandate it, and give more powers and funding to NPAs to make it happen.

Last year, Prime Minister Boris Johnson pledged to protect 30% of the UK’s land and sea for nature. But it’s not credible for the Government to claim that national parks, in their current state, can count towards this commitment. To do so, they need to be much wilder.

We’re calling on UK and devolved ministers to be bold, and mandate wilder areas across all our national parks – to boost biodiversity, sink more carbon and create rich, natural environments for people. The first 70 years have laid the foundations, now it’s time to make our national parks wilder.

Guy Shrubsole is Policy & Campaigns Coordinator at Rewilding Britain.

Explore our Rewilding Manifesto

We need UK Government to Think Big and Act Wild for nature, people and planet.

Learn more

Our vision

We have big ambitions. Find out what we’ve set out to achieve through rewilding.

Our 2025-2030 strategy