Five marine rewilding projects

Healthy seabeds drive a richer marine ecology, which is why these marine rewilding projects are so important.

Our seas are in trouble just as much as our land. At a global level, only 13% of oceanic waters are considered to be truly wild. Elsewhere, the seas have been plundered for vast quantities of fish, and swathes of the sea bed have been stripped of life. This matters because the health of the planet, and ourselves, is bound up with the health of the seas.

But despite the urgent need to reverse the catastrophic decline in marine biodiversity, sea-based rewilding projects are far less common than those on land. The Blue Marine Foundation defines rewilding the sea as ‘any effort to improve the health of the ocean by actively restoring habitats and species, or by leaving it alone to recover’.

Healthy seabeds drive a richer marine ecology, so when habitats of the deep blue recover so does everything that relies upon it. From the slow-growing pink maerl that provides perfect spawning grounds for fish, to flame shell reefs and blue mussel beds, right up to ocean giants like humpback whales feeding in the Minch and the Firth of Forth, life can return.

Here are five exciting marine rewilding projects blazing a trail. It’s not an exhaustive list, but we hope there will be many more to follow.

1. COAST

a community-led no-take zone in Arran

13%

of oceanic waters are considered to be truly wild

The Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST) is a world-renowned example of how a community can protect and restore a marine environment under threat from overfishing, and in the process support local businesses.

To reverse the decline of fish stocks and the destruction of marine habitats in Arran’s seas, COAST spearheaded a campaign which led to Lamlash Bay being listed as a no-take zone and later the wider area becoming Scotland’s first Marine Protected Area. It gave citizens a voice in a debate that has been dominated by the commercial fishing industry.

Left to rewild, lobster and scallop numbers quadrupled in the no-take zone and scallops increased six-fold in the larger Marine Protected Area. Divers also spotted a cuckoo ray, the first seen in the area for 30 years. Fish stocks returned to the area — and with it employment.

Arran’s protected areas began to attract more visitors and, in 2018, COAST opened a Discovery Centre to engage more locals and visitors in marine activities and learning. The Centre welcomed over 12,000 visitors in one year.

2. Native Oyster Network

Restoring UK and Ireland’s native oysters

Oysters are the organs of our sea, cleaning our waters, cycling nutrients and helping protect against coastal erosion. British seas were once full of this charming mollusc, but they have declined to just 5% of their population.

Set up in 2017, the Native Oyster Network includes academics, conservationists and NGOs. They are working to restore the native oyster population across the UK and Ireland by facilitating a collaborative approach, connecting existing native oyster restoration projects, promoting knowledge sharing, and raising awareness of their cultural and environmental value.

3. Seawilding

Community-led native oyster and seagrass restoration

70%

of the oxygen we breathe is produced by seagrasses and other marine plants

Seawilding is the UK’s first community-led native oyster and seagrass restoration project.

Seagrass forms underwater meadows that provide a vital habitat for marine wildlife and stores significant amounts of carbon. Combined with the water filtering powers of native oysters, these marine eco-engineers help protect our waters, boost biodiversity, and tackle climate change. However, we’ve lost 95% of seagrass meadows from UK coastal waters.

Based on the west coast of Scotland at Loch Craignish, Seawilding has begun to restore these populations. They have already restored 300,000 native oysters to the loch and over the last two years have planted approximately 0.2 hectares of seagrass.

Their best-practice restoration methodologies are also being rolled out to other coastal communities in Scotland. Through citizen science initiatives and a close relationship with local schools, community groups, organisations, and academic partners, the project also works hard to help everyone understand marine science.

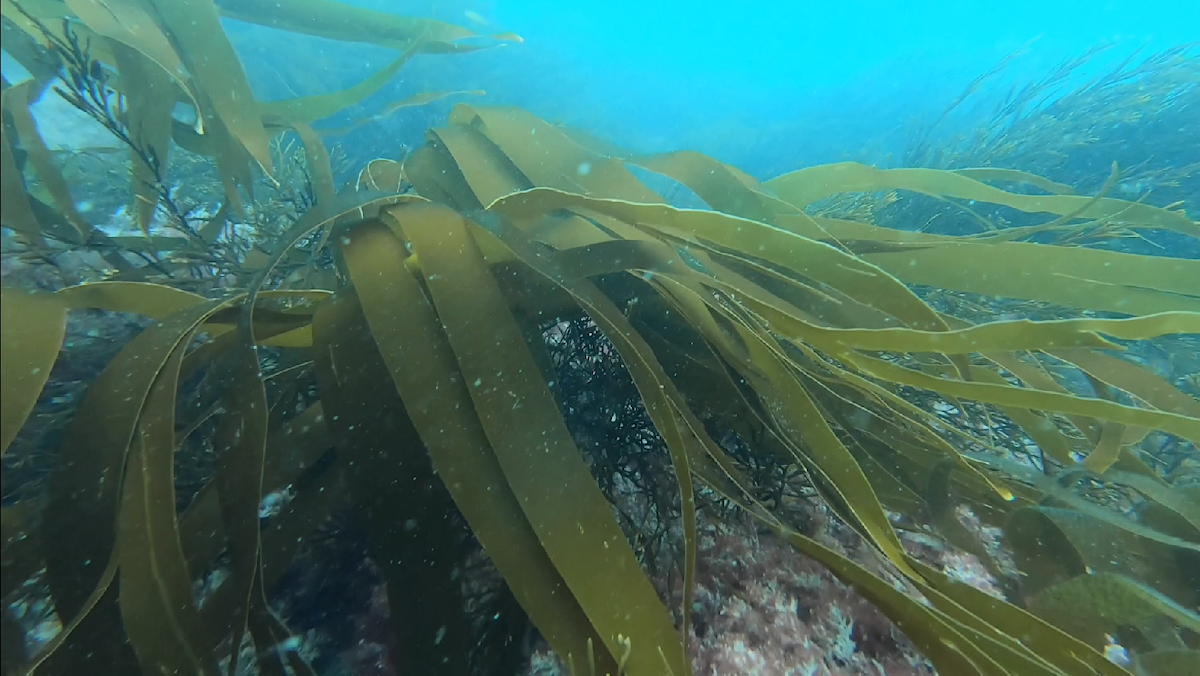

4. Sussex Kelp Recovery Project

Helping our kelp

Kelp is a type of seaweed that can form magical underwater forests. These ‘kelp forests’ are one of the most biodiverse and productive ecosystems on our planet, drawing down and locking in carbon, filtering pollution, and supporting marine life. They were once abundant along the Sussex coastline, but now because of trawling and other human events only a few pockets remain.

The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project launched in collaboration with national and local organisations including Sussex Wildlife Trust and Blue Marine Foundation to help recover this ecosystem.

After successful campaigning from the Help Our Kelp partnership, supported by Sir David Attenborough, a byelaw to protect the Sussex coastline from trawling came into law in 2021.

Kelp and marine life now have a chance to recover along the Sussex coast. Scientists and researchers are studying how the sea bed is changing as kelp recovers, and also the economic and social benefits this brings to the local communities and fisheries.

5. UK Sturgeon Project –on a mission to recover the dinosaur fish

Sturgeon have existed for millions of years, outliving the dinosaurs. They are an important indicator of water quality and by eating dead and decaying organic matter they help clean their marine environment. European sturgeon, often called the prehistoric or dinosaur fish, are now a critically endangered species, but were once one of the most widespread of the sturgeon species, migrating up UK rivers in great schools to spawn.

The UK Sturgeon Project was launched in 2020 to help restore the native European Sturgeon species. They are investigating the feasibility of a sturgeon reintroduction in UK waters and collaborating with European counterparts on restoration efforts in mainland Europe. The project also collects sightings of sturgeon in UK waters, and one day they may be a common sight in our rivers once more!

Ocean report

Blue carbon: Ocean-based solutions to fight the climate crisis

Rewilding 101

Start here to learn all about rewilding, what it looks like and what it can do.

Why rewild

Our vision

We have big ambitions. Find out what we’ve set out to achieve through rewilding.

What we do

Rewild your inbox

Wise up with the latest rewilding news, tips and events in our newsletter.

Sign up now